Do Not Pass Go! Do Not Collect $200!

- Dennis L. Peterson

- Feb 6

- 4 min read

Last month's recent snow/sleet/ice storm brought back memories of childhood snow days. Days of no school and a lot of sledding until our toes, fingers, and noses were nearly frostbitten. And when we finally came inside to thaw our appendages, dry our wet clothes, and eat hot food, there were interminable sessions of playing Monopoly.

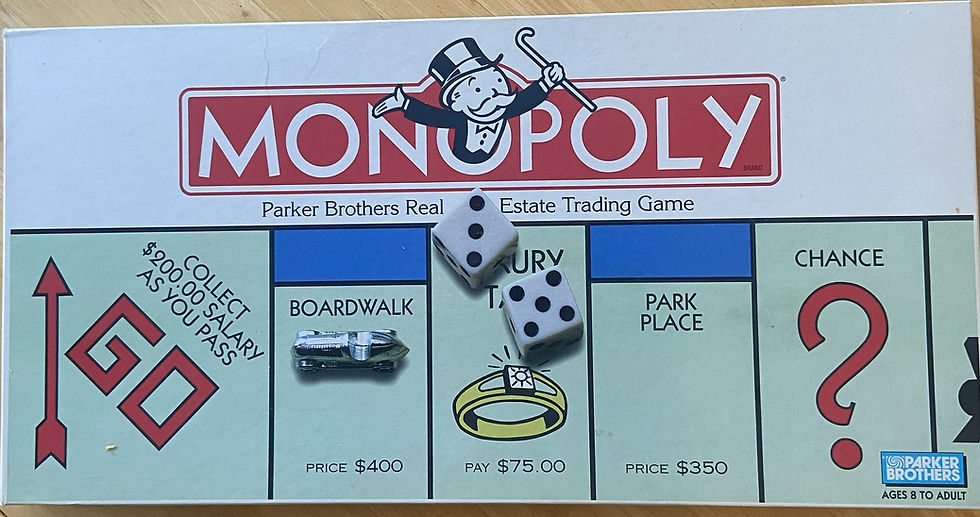

Coincidentally, today marks the anniversary of when that board game first went on sale in 1935.

The game originated with Lizzie Magie's early game called "The Landlord's Game," the board of which was designed by Charles Darrow. Apparently, it wasn't a flashing success, but the Parker Brothers company saw promise and bought the rights to it from Magie and Darrow. They redesigned the board and began selling it on February 6, 1935, long before they patented it on December 31 of that year.

The Parker Brothers' version featured 40 spaces on the board and eight to ten markers for the players. Those markers included a rearing horse, a cannon, a warship, a shoe, a dog, a wheelbarrow, a top hat, an iron, a race car, and a thimble (Mother's favorite).

The spaces featured 28 different properties, the values of which ranged from the "low-rent district" (Baltic and Mediterranean avenues) to the "upper-end" properties (Park Place and Boardwalk). They also included four railroads, two utilities, three "Chance" spaces, three "Community Chest" spaces, and a "Luxury Tax" space. The Chance and Community Chest spaces required the player who landed on them to draw a card from the board and follow its instructions, sometimes to his or her benefit but sometimes not.

Tossing dice, the players advanced around the board and had the opportunity to buy the property on which they landed - or pay rent to the owner if another plaqye3r already owned it. If a player owned all properties of a single color, he or she could build houses or hotels on them - for a price, of course - and collect rent from whoever landed on them. If in a financial bind, he could even mortgage a property, but if he did that, he couldn't collect the rent on it until he'd paid off the mortgage.

On the corners of the board were some surprises. One corner read, "Go." It was where everyone began the journey around the board. Also, every time after starting the journey a player passed that point, he could collect $200 from the bank, sort of a reward for making it around the board again. With that money - if he saved - he could buy properties and build houses or hotels on them, thereby collecting more money in rent payments from those who happened to land there.

Another corner read, "Free Parking." Landing there offered no benefit other than safety because there was no rent or penalty assessed.

A third corner read, "In Jail" or "Just Visiting." Landing there presented no penalty other than the loss of a turn, unless the player had had the misfortune of having drawn a "Chance" card that said, "Go directly to jail. Do not pass go. Do not collect $200," or had landed on the space that read "Go to Jail."

We kids invented our own rule to add an incentive for continuing the game when it had begun to get tedious and some players were itching to return to the sledding slopes. We decided that whenever a player had a fine or other monetary penalty to pay, rather than paying it to the bank, he would put the money in the middle of the board. Whoever landed on "Free Parking" was awarded the monies that had been collected in the "pot" in the middle.

Sometimes such "great ideas" that begin with good intentions produce unintended consequences. One unforeseen side effect of our motivational new rule was that after a while, the bank failed because of its reduced income!

As games wore on, sometimes for hours, my sister would threaten to quit after she had squandered all her money by making unwise decisions. (She had never had the benefit of sitting under the economic teaching of Dr. Stuart Crane or reading Human Action by Ludwig von Mises. Neither had I, for that matter, but that would come later.) To keep her in the game, I often surreptitiously slipped her money under the table. Unfortunately, that did nothing to improve my own financial situation. Rather, it had the opposite effect and just delayed the inevitable. But it kept her in the game for a while longer.

Because a full, complete game took so long to play, I eventually gave up Monopoly after a while in favor of a more exciting game that was more to my historical liking - Risk. I learned, however that it, too, can become interminable and addictive. It was so addictive, in fact, that I found myself playing in Risk tournaments when I was in college - during exam week, when I should have been studying.

Now I can't remember the last time I played either game. But snow days bring back memories of them, especially Monopoly.

Comments